Recent years have demonstrated the critical role of fiscal policy in shielding households and the economy from large shocks, but the costs can be large. Many Asia-Pacific countries currently face substantial challenges, including lower growth and the impact of aging and climate change, while having to manage high or rising public debt.

Against this backdrop, upgrading fiscal frameworks—regulations and procedures that influence how fiscal policy is planned, implemented, monitored, and assessed—could make fiscal policy more effective in managing the risks and addressing challenges amidst tighter budgets.

Our new research, including an assessment of the existing fiscal frameworks, provides insights into how Asian-Pacific countries can strengthen fiscal rules and frameworks.

Managing large shocks

Asia-Pacific countries took unprecedented fiscal measures in response to the global financial crisis, the Covid pandemic, and the cost-of-living crisis in the aftermath of the pandemic.

Such actions were a departure from the past role of fiscal policy in the region. In particular, fiscal policy can help stabilize the economy by being countercyclical—that is, the budget deficit increases (declines) when the economy weakens (strengthens), which helps in stabilizing the economy. Or policies can be procyclical: deficits decrease when the economy weakens, and vice versa, which exacerbates economic fluctuations.

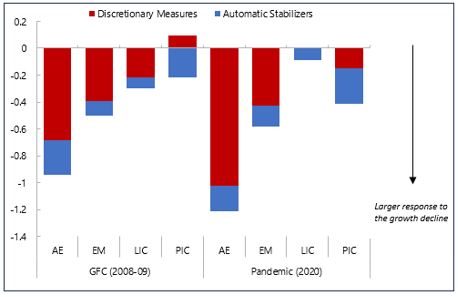

Policies became significantly more countercyclical after the global financial crisis (GFC). This has been the case especially among advanced economies (AEs)—for a 1 percentage point decline in real economic growth, the fiscal balance is estimated to deteriorate by almost 0.6 percent of GDP—reflecting both automatic stabilizers (for example, changes in income tax and unemployment benefits due to changes in economic activity) and discretionary measures (for example, cash transfers to households or subsidies to firms).

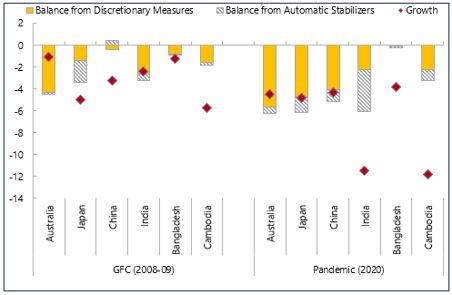

The degree of countercyclicality was especially large during the GFC and the pandemic (Figure 1). AEs and emerging markets relied mainly on discretionary measures as automatic stabilizers were too limited. For example, Australia and Japan adopted large discretionary policies in response to the pandemic, with overall balances deteriorating by more than 6 percent of GDP in 2020 relative to the previous three-years. Fiscal deficits also expanded significantly in China and India. Among low-income countries, fiscal responses tended to be more muted, but there were differences: fiscal balance in Bangladesh barely changed, while the deficit expanded in Cambodia.

Figure 1. Fiscal Policy in Asia-Pacific the Global Financial Crisis and the Pandemic

|

1. Change in Fiscal Balance per country group (Percent of GDP, per 1 percentage point decline in GDP growth) |

2. Changes in Fiscal Balances and Economic Growth for selected countries (Percent of GDP; percentage points) |

|

|

Source: Authors’ calculations.

Note: In panel 1, red and blue bars denote the estimated changes in fiscal balance from discretionary measures and automatic stabilizers, in response to 1 percentage point decline in GDP growth, based on 5-year windows that include the GFC (2008 and 2009) or the pandemic (2020). In panel 2, orange and patterned bars denote the deviation in the balances from the previous three-year average, and red diamonds denote the deviation in growth from its previous three-year average. See Annex 1. AE = advanced economies; EM = emerging markets; GFC = global financial crisis; LIC = low-income countries; PIC = Pacific Island countries.

Fiscal frameworks under pressures

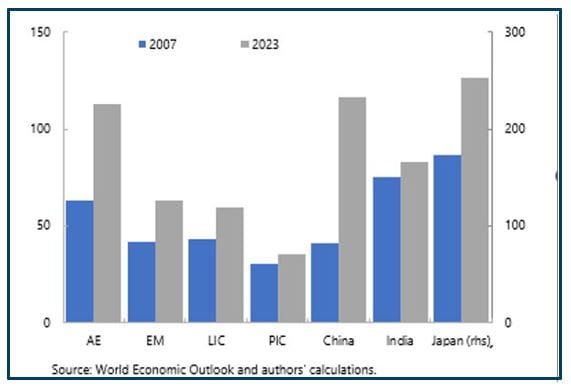

The responses to the crises, however, came at a cost, with public debt rising continuously since the GFC. Debt levels in Asia-Pacific are on average 50 percent of GDP higher relative to 2007 among AEs and 15-20 percent of GDP higher among others (Figure 2). For example, the level of debt more than doubled in China to above 100 percent of GDP, and in Japan rose above 250 percent of GDP.

The large shocks, especially the pandemic, have also highlighted that fiscal frameworks have not been sufficiently robust. For example, 23 countries in the region that had fiscal rules tended to comply more with the rules, or have smaller deviations, than their peers in other regions before Covid hit--the median deviation from the debt ceiling in Asia-Pacific was just over 5 percent of GDP.

However, governments bypassed or modified their fiscal rules to address the pandemic. As debt levels had already been rising in the Asia-Pacific region, the effects of and policy responses to the pandemic led to large deviations from or suspensions of fiscal rules. Most governments breached the deficit rules in 2020-22, with the median deviation reaching 6.6 percent of GDP and larger than in other regions.

The tools used to respond to crises, including social safety nets, were underdeveloped in some countries, requiring ad-hoc actions that were not always well targeted or timely. In some cases, extra-budgetary measures were larger than budget support during Covid. In addition, some countries did not have clear exit strategies, which, in some cases, led to procyclical expansionary policies after the shocks.

Figure 2. Public Debt Soared in Asia-Pacific since the Global Financial Crisis (Mean of respective group, percent of GDP)

Note: AE = advanced economies; EM = emerging markets; LIC = low-income countries; PIC = Pacific island countries; rhs = right scale.

Upgrading Fiscal Frameworks

Governments now face the challenge of managing high debt levels and growing spending pressures to achieve development goals and to address demographics and climate change. In addition, the weaker growth outlook and higher interest rates imply that the level of debt that governments can sustain is lower.

Such challenges make it more pressing to strengthen medium-term fiscal frameworks. While many countries have some form of medium-term fiscal frameworks—encompassing a fiscal plan or strategy, medium-term projections, and targets or rules that guide annual budgets—they are not always well-developed or effective. Upgrading medium-term fiscal plans will help to identify what measures are needed today to achieve future goals. For countries with high or rising debt risks, it would help develop credible plans to gradually reduce debt, while avoiding disruptive fiscal adjustments. For low-income countries, it would help build support for a development strategy, including enhancing domestic revenues.

Improved fiscal frameworks should include better assessment of risks and necessary fiscal buffers, improved safety nets, and other crisis tools to allow for timely and targeted responses to adverse shocks. Expanding the coverage and improving the quality of government finances and debt statistics would also improve fiscal management.

A risk-based fiscal rules approach could make rules more robust. It requires developing medium-term plans and fiscal rules that are more ambitious depending on the degree of risks, building enough fiscal buffers in good times, and well-designed escape clauses.

Governments also need to better integrate the effects of aging and climate change in fiscal frameworks. Population is already shrinking in China, Japan, and Korea, and population growth will turn negative in many developing economies over the next 15 years. The region also includes some of the most vulnerable countries to climate change. Improved medium-term fiscal frameworks can help reflect these effects and the tradeoffs from alternative reforms, including in the transition to a green economy.

Some of these reforms are difficult and will take time, but are critical for a more impactful and effective fiscal policy.